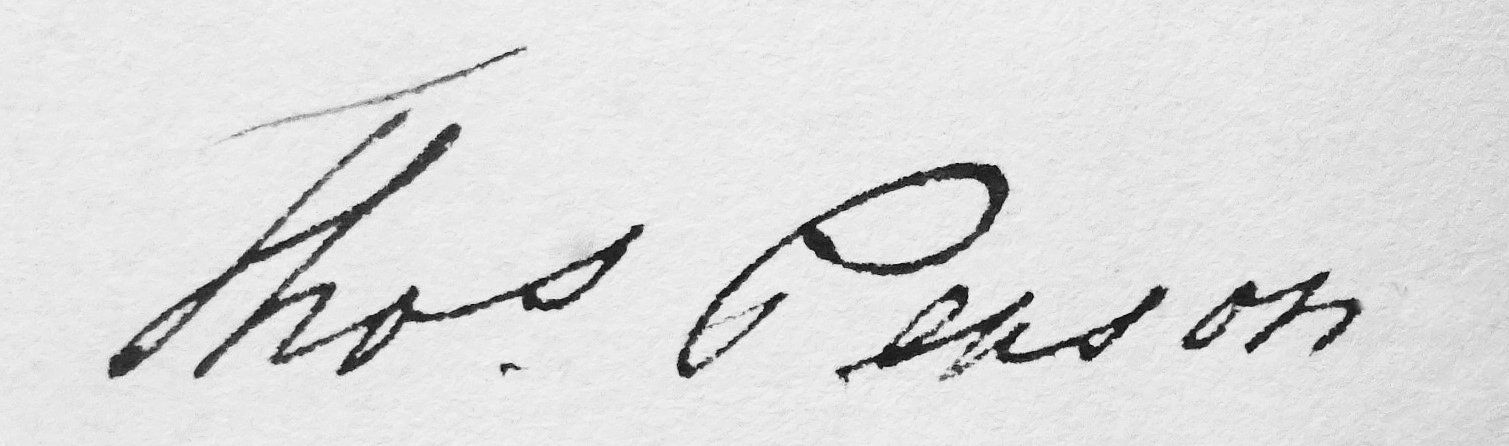

Thomas Penson

Thomas Penson was born in Wrexham on 5 May 1790. He was the second of the three children of Thomas and Charlotte Penson, with an older sister, Jane, and a younger brother, John William Todd.

Thomas Penson senior was an auctioneer, builder and engineer, living and working in Wrexham, and involved in the construction of a number of major buildings in north Wales. He and his son Thomas were both members of the East Denbigh Local Militia, and in February 1810 a list of new commissions included ‘Thomas Penson, sen, Esq., to be Captain’ and ‘Thomas Penson, jun, Gent., to be Ensign’.

In around 1809 Thomas junior studied with Thomas Harrison, the Chester architect and bridgebuilder, and won a competition for the design of a bridge over the Dee. Further mentoring took place in 1813 when Thomas junior took over the construction of a bridge over the Dee at Overton under the supervision of John Carline II from the Shrewsbury bridgebuilding dynasty. Thomas Penson senior, as county surveyor of Flintshire, had designed a single span bridge at Overton in 1810, but it had collapsed during construction. He was unwilling to meet the terms for the rebuilding of the bridge set by the Flintshire justices, and lost the contract, which was taken over by his son.

Marriage

In 1814 Thomas Penson junior married Frances Kirk, daughter of the wealthy ironmaster Richard Kirk. Kirk had come from Derbyshire in the 1770s, and became one of Denbighshire’s early industrialists. He lived initially at Bryn Mally, near Wrexham, and rapidly expanded his land holdings, operating a number of collieries. He and his wife Ellen were members of the Chester Road Presbyterian Chapel in Wrexham, where their twelve children were baptised. It would seem that Penson and Kirk got on well, as Kirk asked Penson to design property for him, and Penson was one of the executors of Kirk’s will.

After their marriage Thomas and Frances lived in Overton Cottage (now Min-yr-Afon), overlooking the Dee where Thomas was building Overton bridge. Six of their ten children were born while they were living in Overton Cottage, and were baptised in Overton church. Thomas is recorded in the church register as a ‘builder’.

Overton Cottage was owned by Francis Richard Price (of the Bryn-y-Pys estate) and looks in essence like an early nineteenth century house, but there is evidence in the north-east wing that it was remodelled from an existing building. The style is similar to some of Penson’s other work, notably Aberhafesp rectory, so it is possible that he carried out the remodelling. Could this have been a commission from Price (maybe suggested by Penson) after the family had moved to Oswestry in about 1823?

Family

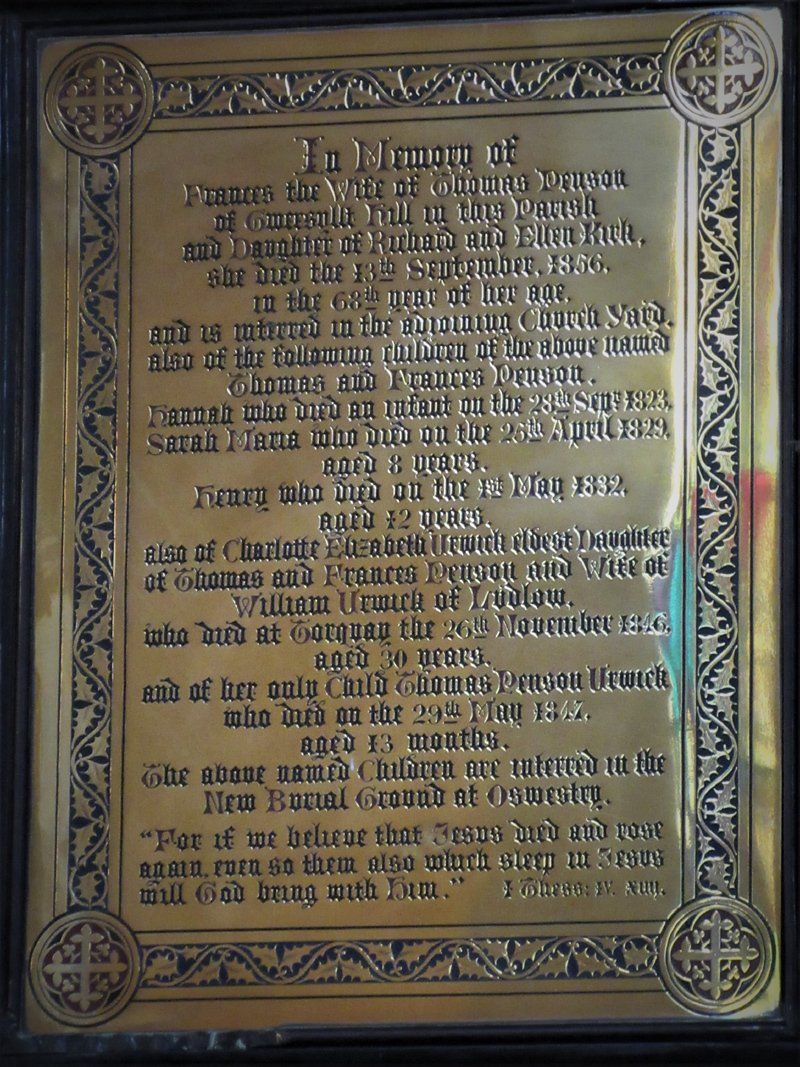

Thomas and Frances seem to have had a happy marriage, and when she died in 1856 the wording of her death notice in local papers was more emotional than was usual at the time. Four of their children pre-deceased them, one dying as a month-old baby, two in childhood, and one aged thirty.

The Pensons involved themselves in their children’s and their wider family’s lives. In 1841, for example, Thomas rallied influential contacts – including the Montgomeryshire MP, Charles Watkin Williams Wynn – to provide references for their youngest son, James Owen, to ensure that he was taken on as a cadet in the East India Company’s Military Seminary. With Penson’s background in the local militia, this may have been a career choice close to his heart.

And in 1846, when their oldest daughter, Charlotte, died aged thirty, a few months after giving birth to a son, the Pensons took the baby to live with them. Charlotte’s widower, solicitor William Urwick, although he had remarried, was part of the family funeral party when Thomas himself died, over a decade after Charlotte’s death.

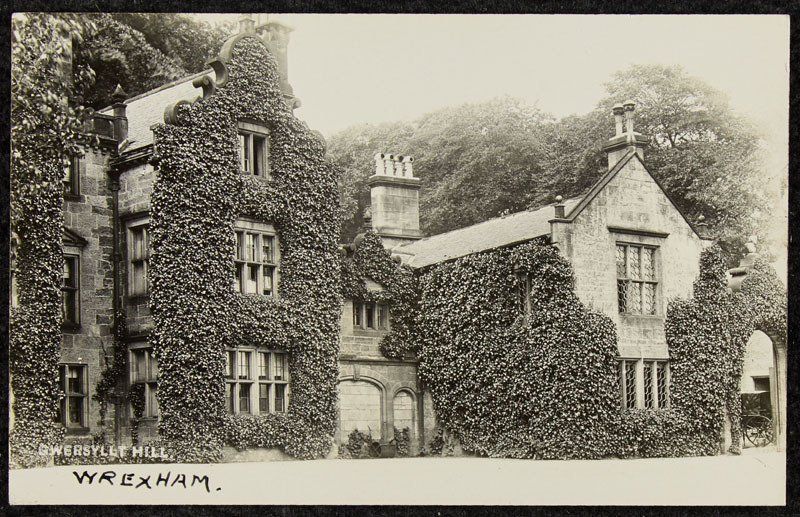

Thomas’s only brother, John William Todd (usually known as William) died aged thirty, in 1826, and his widow, Catherine, four years later, leaving three very young children, a daughter and two sons. The older boy died in his teens, and it is not clear what happened to the younger boy, but in 1852 William and Catherine’s daughter, also Catherine, was married from Gwersyllt Hill, Frances and Thomas’s home, with her cousins in attendance.

Thomas’s relationship with his oldest son, Richard Kyrke, however, was frequently volatile, starting in 1838 when Thomas took a young Richard to court over work that Richard had not dealt with as his father wanted. Shortly afterwards Richard decamped to London, to train as an artist. There were to be further fallings out between father and son over the years.

Career: starting out

While Thomas and Frances were living in Overton Cottage, Thomas was on hand to oversee the rebuilding of Overton bridge, but he was also active on a number of other fronts. Nearby he designed a new north aisle for Overton church, which was completed in 1819.

He quickly achieved a regular income by becoming county surveyor for Montgomeryshire in 1817, and of Denbighshire in 1819, both of which posts he held until his death in 1859. He also became surveyor for the Montgomeryshire Turnpike Trusts, in charge of well over 300 miles of road.

As well as securing long-term jobs, he started ensuring that he became known by people who might be useful to him in the future. In 1818, for example, at a quarterly meeting of the Maelor Hundred Savings Bank, in Wrexham, he offered his services to the president, the Rt Hon Lord Kenyon, to make, at his own expense ‘the Room where this Meeting is held, more commodious.’ The offer was accepted.

Work as a county surveyor

An important element of the work of local justices of the peace was to ensure that bridges and roads in their county were fit for purpose. During the eighteenth century there was little distinction at this level between the work of builders, surveyors and architects, and any one of them could be asked to draw up plans for and oversee any construction work that was needed, usually on an ad hoc basis.

As demand for building work increased justices began to employ surveyors with either a specific responsibility for bridges, or for all types of construction, including prisons. By the early nineteenth century both Montgomeryshire and Denbighshire paid a salary to a county surveyor who dealt with all building works, including roads, providing designs and plans, and overseeing construction.

Penson’s first bridge as county surveyor for Montgomeryshire was Pont Llogel, completed in 1817, and he had designed and completed another seven bridges in the county by 1827, including Newtown Long Bridge (before the iron walkway was added). His bridge designs are very successful – they are clean, balanced, and functional.

Both Montgomeryshire and Denbighshire needed improvements and repairs made to roads and bridges. An advertisement, for example, for Denbighshire County Works of May 1825, seeking tenders from contractors for bridge and road repairs lists twelve bridges needing work, with ‘particulars from the office of Mr Penson, Oswestry’. An advertisement from October of the same year shows Penson working on behalf of the Turnpike Trust, looking for contractors to make a ‘new line of road’ at New Bridge, on the Dee.

His work as county surveyor for both Montgomeryshire and Denbighshire included work on gaols, lock ups, and accommodation for staff, and work for the justices themselves. In 1836, for example, he remodelled the assizes courtroom in Welshpool (previously the upper part of what is now the town hall), making a ‘new, spacious room, lighted from the roof’, and costing £1,200 (around £140,000 today). While, rather more mundanely, in 1838 he produced plans for a ‘lock up house in Denbigh with nine cells and an apartment for the keeper’.

Similar work occupied him for the rest of his life in his county surveyor role.

Private practice

Doubtless the fact that Penson was county surveyor and worked on high profile projects helped bring in private commissions. And he took on a lot, possibly to the detriment of his ability to pay attention to detail.

In 1837 – as a result of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 – he took on the design and construction of four workhouses simultaneously: at Llanfyllin, Caersws, Ruthin, and Conwy (though the workhouse at Conwy was not built until 1850). Inevitably, with such a workload, he ran into problems – going over budget at Llanfyllin by over fifty percent, and with contractors and materials at both Llanfyllin and Caersws.

He designed eight churches between 1840 and 1853, some in his idiosyncratic Romanesque style, and some in his Gothic style. Full details are given elsewhere on the website.

Penson certainly built private houses, but there is little surviving evidence of what or where apart from advertisements where he asks for contractors to tender for work on, for example, ‘a country villa’. He was also invited to remodel larger old houses, often using his neo-Jacobean style – again, details are given elsewhere on the website.

In 1839 he became an associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE), and 1848 a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

Life beyond work

Thomas Penson was keen to make his mark in society. By the 1830s his name ‘Thomas Penson, Esq’ and ‘Thomas Penson, Gent’ is increasingly found in lists of subscribers to charitable causes, or testimonials to the great and the good, and occasionally on organising committees. In January 1835, for example, ‘Mr Penson and the Committee of Management’ were toasted at the celebratory dinner for their part in the events marking the success of ‘Sir Rowland Hill, Bart, and W Ormsby Gore, Esq’ in being returned to Parliament in the general election.

In October 1835 (after the introduction of the Municipal Corporations Act of that year, which ensured that town councils were elected by ratepayers, and that there were annual elections of a fixed proportion of councillors) Thomas Penson was elected to Oswestry town council.

In February 1836 it was reported that Mr Penson moved ‘That it is the opinion of the Council that the Mayor be allowed a salary,’ and he proposed £50. It was fiercely debated, but in the end eight councillors voted for, and seven against. Thomas Penson became mayor in 1840. His inaugural dinner was studded with the local great and good, including aristocracy and MPs – people he wanted to impress.

From the late 1830s onwards Penson became increasingly interested in the new railways, as did both his architect sons (see separate entries). In particular he was involved in the Shrewsbury and Birmingham railway company’s plan to make a direct link between London and Dublin using a route from Shrewsbury to Bala and on to Port Dynllaen as the crossing point. In 1839 Penson was part of a delegation to Ireland to discuss the potential project – a delegation that included the Hon R Clive, MP, and Mr Ormsby Gore. The project would have improved railway access in Wales, but this was also one of its drawbacks, as financial backers did not see enough take-up in terms of either passengers or cargo from the areas it crossed. In the event, railway engineer Robert Stephenson’s plan to take the route from Chester to Holyhead was eventually chosen, and received its permission in 1845.

In 1839 Richard Kirk, the father of Penson’s wife, Frances, died, and left his daughter what he called his ‘Gwersyllt Hill mansion’, where he had lived towards the end of his life. Penson extensively remodelled Gwersyllt Hill the house in his preferred neo-Jacobean style (sometimes called his ‘Jacobethan’ style). Eventually it became the Pensons’ main residence.

In 1850 he gave Gwersyllt parish land for a new church and a school, both of which he designed himself.

Later life

Penson continued working on many projects and being part of public life right up to his sudden death in 1859. The day before he died he was energetically addressing a meeting in the town hall in Wrexham recommending that a voluntary rifle corps for Denbighshire should be formed so that they were prepared for any attack from abroad. He said that he was speaking as a founder member of the earlier Denbighshire militia, which had been formed against the threat of a French invasion from Napoleon, and was ’the oldest soldier present at the meeting (cheers)’.

Thomas Penson was sixty in 1850, and had not slowed down.

In his early sixties he was still working on the remodelling of Vaynor, the building of Rhosllanerchrugog church, and the tower of St David’s in Denbigh, as well as his day-to-day work on roads and the repair and building of bridges. In 1859, the building of his planned bridge at Cilcewydd, just outside Welshpool, was in progress, and was completed by Richard Kyrke Penson, who was briefly county surveyor for Montgomeryshire after his father’s death.

A controversial personality

It seems that Penson had always had a quick temper and aggressive reactions: way back in 1811, when he was twenty-one, following an altercation with a Richard Eyton Edwards, Penson was summoned before the court in Wrexham for incitement, having issued Edwards with a written challenge to fight a duel.

It is clear from newspaper accounts of the numerous law suits he was involved in throughout his life, that Penson could be abrasive and difficult, and was very reluctant to back down. He could be high-handed with people he thought of as inferior to him, especially when dealing with contractors. During the building of Llanfyllin workhouse, for example, Penson was at one point accused of treating one aggrieved contractor with ‘neglect and contempt’.

There were also suggestions that Penson was not scrupulously honest.

In 1840 Isaac Evans, employed as a contractor for work on Llandulus bridge, took Penson to court for deliberate underpayment of his bill, refusing arbitration as he wanted to ‘bring him to court and expose him’. The judge found in Evans’s favour. Subsequent letters to the Chester Chronicle hinted that Penson was ‘punishing’ Evans for refusing to pay him a backhander (‘jobbery’), and called for ‘the full circumstances to be laid before the public’.

In 1852 one of Penson’s neighbours at Gwersyllt, Richard Thompson of Stansty Park, gathered meticulous evidence that he felt proved that Penson had diverted materials paid for by the county to repair Bangor bridge to the remodelling of Gwersyllt Hill. He resolved to take this to the justices, but feared that it would not be believed, as Penson was too well thought of by those in power (whose good opinion Penson had assiduously cultivated throughout his life).

Richard Thompson’s fears would seem to have been well-founded. There was no mention of the accusations, and a few months later Penson was made a deputy lord lieutenant of Denbighshire, a position he relished.

Stressful final years

However little attention Penson seemed to pay to public opinion, he experienced in his sixties a mix of private problems and public criticism that must have undermined the energy that he had always been noted for.

In 1849 the career of his son James in the East India Company’s Bengal Army came to an ignominious end. ‘Ensign James Owen Penson of the 19th Regiment Native Infantry, who was tried by a General Court-Martial at Meerut, convicted of having cut and wounded Munsasam Peon, and sentenced to imprisonment in the fortress of Agra for two years, is dismissed from the Honorable Company’s Service.’ Penson tried every avenue he knew to have his son’s sentence reduced, and succeeded, but the shame remained, and he later cut James out of his will.

In 1856, his wife, Frances died.

All this was probably enough to distract Penson from keeping on top of detail in his work. There were complaints, for example, that he paid little attention to ensuring that roads were kept maintained, and could not be contacted. The sense that finally his work as county surveyor could have been more committed was suggested after his death when the Montgomeryshire justices specified that the next county surveyor should not be a surveyor in any other county, and should live in Montgomeryshire.

The Caerhowel bridge disaster in 1858, however, brought very public criticism of Penson. The bridge was swept away in the bad floods of 1852, and Penson’s design for a replacement bridge was rejected by the justices in favour of a cheaper design by Dredge & Stephenson of London, who used an Edinburgh contractor to build the bridge. Penson was angry, and seemed vindicated when the bridge collapsed in 1858, killing one person. However, in the enquiry that followed, much criticism was directed at Penson himself for not supervising the construction work properly as county surveyor, or inspecting the quality of the iron used. It was said that Penson did not go to the site himself, but left any inspections to his less experienced assistants.

After his death in May 1859, a tribute paid to Thomas Penson at the next Quarter Sessions meeting of the Montgomeryshire justices by the chairman mentioned his skill and care with building bridges in difficult places – bridges that had impressively stood the test of time. He ended by saying ‘that he was sure that the justices would join him in a tribute of respect (applause)’.

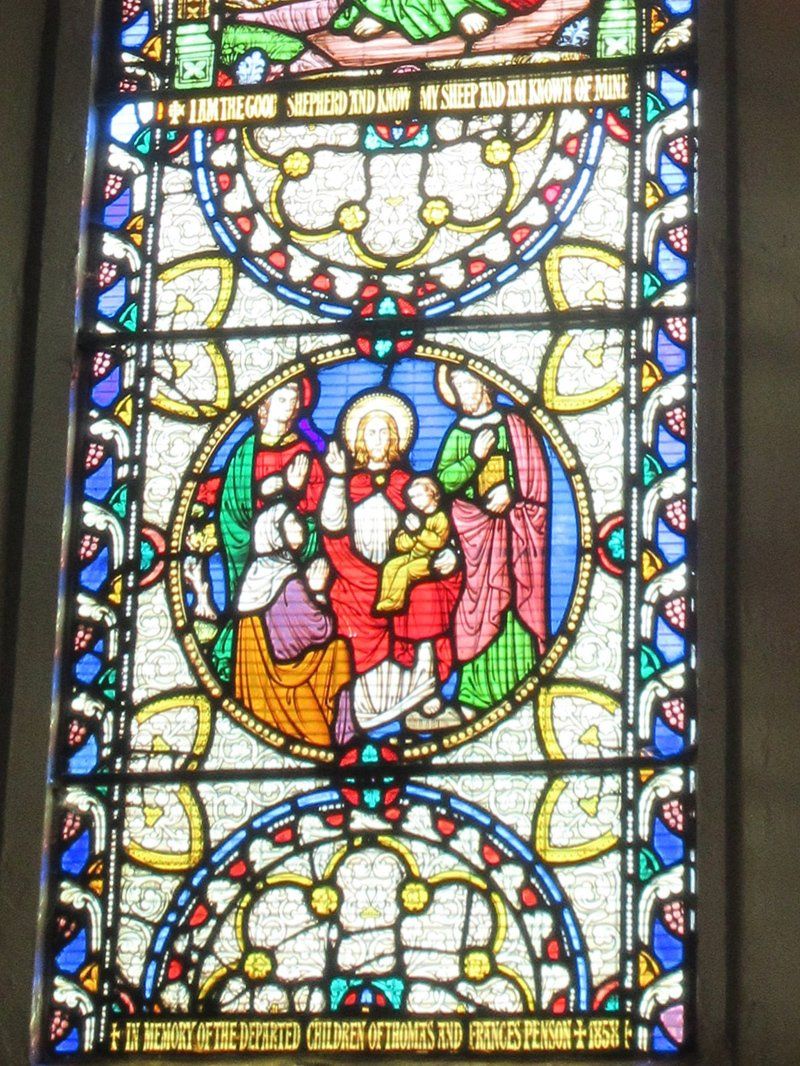

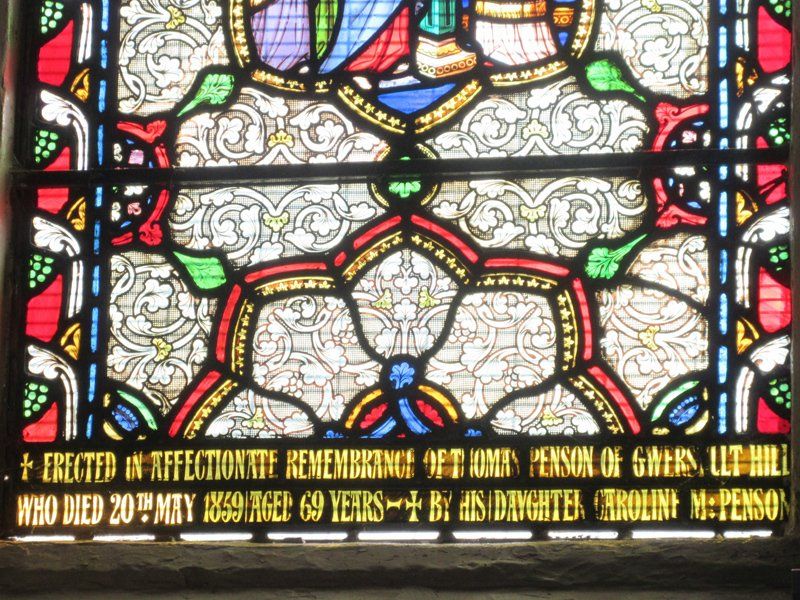

Penson was buried, with his wife, at Gwersyllt church, and his daughter Caroline, who inherited Gwersyllt Hill, commemorated him in a stained glass window in the church, a companion piece to the windows commemorating Frances and the children who had predeceased them.

Penson left over £16,000 (the equivalent of over £2 million today). Unsurprisingly, the divisive nature of his will resulted in his children challenging it in court.

Text: Frances Ward

Sources

British Newspaper Archive (British Library)

Edward Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales, Clwyd, Yale University Press 1994

Tithe maps for Overton parish (1839) and Gwersyllt township of Gresford parish (1844)

Robert Anthony: Penson’s Progress, Montgomeryshire Collections, Powysland Club, 1995

Parliamentary Papers, vol 19: Select Committee on Turnpike Trusts and Tolls, interview with Thomas Penson, May 1836 (gives precise dates for his county surveyor appointments)

Census and parish records via ancestry.co.uk and findmypast.co.uk

Christopher Chalklin: English Counties and Public Building 1650-1830, The Hambledon Press 1998

Tony Plunkett: Unpublished family research about Merrick Shawe Plunkett (Merrick Shawe Plunkett married Penson’s youngest daughter, Caroline, after Penson’s death.)

Letters written by Richard Thompson in the Denbighshire archives

The Bank of England inflation calculator